Climate Change - Review

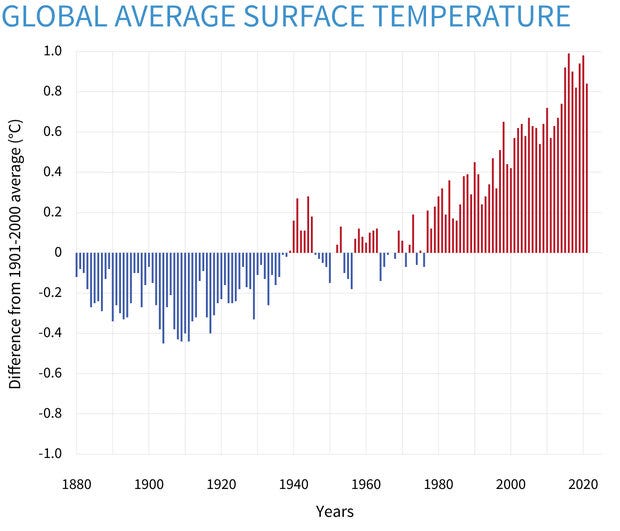

Climate changes are long-term shifts in climate patterns indicative from things like temperature and rainfall. Historically, these changes have been naturally triggered by volcanic eruptions, asteroid impacts or wobbles in Earths orbit. Yet after a stable climate for the last five thousand years or so, the earth has warmed around 1ºC just in the last 150 years (from pre-industrial levels, 1850-1900). This is something entirely different. Why?

First, while natural climate change occurs over tens of thousands to millions of years, today's change is taking place over just a century or two. That means the current speed of warming is the fastest in earths recorded history, being more than 10-20 times faster than natural past climate changes.

The second main difference is the driver behind this unprecedented global shift. This time, no wobbles in earths orbit, volcanoes or asteroids are involved. Instead, we humans are to blame. More specifically, human activities releasing “greenhouse gases” (mainly carbon dioxide [CO2], methane and nitrous oxide) are driving it. Such compounds absorb infrared radiation (as a greenhouse would), thereby trapping heat in the atmosphere and warming the Earth.

Greenhouse gases sustain life on our planet, and their absence would cause a drop of 33ºC in the average temperature on the surface. However, the finely regulated balance of gas levels in our atmosphere ended when we began burning fossil fuels. While CO2 was stable at 280 parts per million (ppm) for thousands of years, today it’s up to ~418 ppm - 50% higher. Last time CO2 levels were so high was about 3 million years ago.

Today’s unprecedented climate change and the negative effects it is having (and will have) on human communities have boosted social and political action. We asked many climate experts some of the most contentious questions on the issue. Is it already too late to avoid a warming beyond 1.5ºC? Can nuclear power or organic farming help us to reduce CO2 emissions at all? Can we hold on to our lifestyle if we are to limit temperature rise? This is what we found out.

Source: NOAA

Meta-Index

2013-2021: All rank in the worlds warmest 10 years on record

45 years: Consecutive years (since 1977) with global temperatures above the 20th century average

36.3: Billions of tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2021 via fossil fuels

380 billion: The amount of emissions in tonnes we can emit to give the world a 50% chance of not exceeding 1.5°C

9: Years until the 1.5degC carbon budget is exhausted if taking 2022 emission levels

1230 billion: The amount of emissions in tonnes we can emit to give the world a 50% chance of not exceeding 2°C

30: Years until the 2°C carbon budget is exhausted if taking 2022 emission levels

24: Countries who fossil fuel emissions declined during the decade 2012-2021 while their economies grew

5.4%: Decline in global fossil fuel carbon emissions during 2020 via COVID impact on economy

5.1%: Increase in global carbon emissions fossil fuel carbon emissions in the following year (2021)

BACKGROUND

How 2°C, then 1.5°C became the warming limit

The science of how humans cause climate change is long and well established, dating back to to 1824 as we write in detail here. How much the world will warm by is also getting more certain as we write in detail here. But what warming target should the world agree too? That question has been plagued with politics and debate.

In 1975, Yale economist William Nordhaus predicted that a warming of more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels would “take the climate outside of the range of observations which have been made over the last several hundred thousand years”. Further studies in 1990 by the Stockholm Environmental Institute argued that limiting climate change to 1°C would be the safest option but deemed this limit “unrealistic” and proposed 2°C as a more practical target. From then, “below 2°C” became everyone’s go-to phrase in climate policy.

This included the discussion board on the first of the 26 Conferences of The Parties (which you have surely heard of as COPs), which took place in Berlin in 1995. The following year, the European Council declared that “global average temperatures should not exceed two degrees above pre-industrial level,” and the world’s first agreement to cut greenhouse gas emissions, the Kyoto protocol, was signed by 193 countries in 1997. More recently, the Paris agreement, signed in 2015 by 197 countries, specifically aimed to “limit global warming to well below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.”

The summoning power of the 2°C was in its pragmatism and its simplicity, which allowed scientists to communicate and policymakers to understand, but reality is more complicated. In a similar way a 1°C or 2°C rise in our body temperature can make us feel unwell, tiny temperature changes can also affect the Earth. Indeed, temperatures have already risen ~1ºC since pre-industrial times, dramatically increasing the Arctic sea-ice melt and glacial retreat, with sea-level rising. From coral reefs to biodiversity, this climate shift is causing big impacts. Going beyond 2°C will also affect humans, and up to 37% of the global population may suffer from an increased intensity and frequency of heat waves, droughts, floods and tropical cyclones. Going beyond 2°C will also affect humans, and up to 37% of the global population may suffer from an increased intensity and frequency of heat waves, droughts, floods and tropical cyclones.

Economically, assets are under risk due to infrastructure, carbon risk and climate damages by the end of the century. Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, has long warned that climate change could cause the next financial crisis while the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in the US last year published a report stating “Climate change poses a major risk to the stability of the us financial system.”

The world’s commitment to tackle climate change is growing, and the technological solutions required for a zero-carbon future already exist. But lots of questions still remain.

CONSENSUS

If we reduce carbon emissions to zero tomorrow, is 1.5degC locked in?

We asked 11 experts and overall it seems unlikely we can limit the world to 1.5°C.

Dr Max Callaghan from Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change reminds us that “we are currently at 1.07 degrees of warming” and “though additional warming is still locked in”, we can avoid surpassing 1.5°C if we “start reducing emissions rapidly now and achieve net zero by the middle of the century.” Dr Callaghan supports this by citing the latest IPCC report, which shows that even if we still release “500 gigatons of cumulative CO2 emissions in carbon budgets” we retain “a 50% likelihood of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.” A similar view is shared by Prof Dennis Hartmann from University of Washington, who writes that “if we zeroed out emissions tomorrow we would likely not exceed 1.5°C.” He argues that “this would mostly be due to zeroing out methane emissions, whose lifetime in the atmosphere is only a decade or two.”

On the other hand, however, Prof Gabriel Filippelli from Indiana University-Purdue University is not so sure. He admits that after stopping carbon emissions “natural processes in the carbon cycle will slowly act to pull out the excess carbon,” but also warns that these processes will take “decades to centuries.” Likewise, Prof Richard B Rood from the University of Michigan “can conceive of scenarios to avoid 1.5ºC average warming” but considers that such scenarios are “unrealistic and require the best-case outcome at virtually all points of uncertainty.” This is due to the many (and complex) processes involved, such as “how rapidly the oceanic and land processes, which remove carbon dioxide, might work” or “how much the Arctic and Antarctic have been altered by warming.”

Finally, Dr Michael Wehner from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is more pessimistic and urges us to “get real.” In his view, “it seems highly unlikely that the drastic emissions reductions required to stabilize the climate to 1.5 will be palatable to the governments of the high carbon emitting countries.”

CONSENSUS

Is it possible to sustain our current standards of living and also slow down climate change?

Humans are the primary driver of recent climate change (see our factcheck here). Is there any chance we can minimise our impact on climate without changing our lifestyle?

Prof Filippelli gives us his 4 bullet points of must-dos to tackle this crisis: “We need to:

change our food systems [...],

change how we power the electrical grid [...],

take gasoline and diesel out of our transport industry and [...]

convert all home-based appliances to electric.”

He also points out that “the last three actions can be taken with little impact at all on our lifestyles” whereas “the first action will require a major change in how we view climate-friendly foods.” Prof Dennis Hartmann from University of Washington agrees, and highlights that our quality of life will not only remain unchanged but “improve if we decarbonize the energy economy wisely.” Prof Gab Abramowitz from UNSW Sydney adds that by “transitioning to renewable electricity in a cost effective manner [...] standards of living will only improve.”

Less optimistic is Dr Callaghan, who warns that we might still need to give up on some things since “some sectors, like international air travel, are hard to decarbonise.” He also points out that scholars “believe that sustainable societies are only possible if rich countries shrink their economies (otherwise known as degrowth).” This brings us to a key point: will this be possible to actually improve living standards, and would this be compatible with fighting climate change?

Dr Lisa Schipper from the University of Oxford, who acknowledges that “some people are not living with good standards, and for them things will get worse with climate change.” She explains that “for those of us who are living well, we may have to rethink exactly what we need to feel good” and points out that “the fundamental human rights are what we need to keep in mind.” Similarly, Prof Roger Jones from Victoria University says that “for the higher-end consumers and those on higher personal incomes – their ‘standard of living’, i.e., levels and structure of consumption has to change.” Finally, Prof Rood considers that “many in the world need to improve their standard of living.” For those, energy is the answer so “address both climate change and sustaining and improving the standard of living requires decarbonizing our energy supply.” This process may take long, unfortunately, so Prof Rood fears that “in the short term, decades, we cannot universally sustain and improve standards of living and slow down climate change.”

What experts fully agree with is that, as Dr Callaghan writes, “it will not be possible to sustain our current standards of living if we do not slow down climate change. Rapid reductions in emissions are the best way to safeguard living standards.”

CONSENSUS

Can the world decarbonise without nuclear power

Nuclear power was (and often still is) perceived as dangerous, but it is also true that it produces about the same amount of CO2-equivalent emissions per unit of electricity as wind, and only one third of the emissions per unit of electricity when compared with solar. For that reason, nuclear power is considered by some scientists as a crucial weapon against climate change, which could allow us to maintain high levels of energy production with no greenhouse gas emissions. Others, however, claim that nuclear power is still dangerous and contaminant and that it is not needed to achieve carbon reduction.

Our experts were very much split on this issue. For example, both Prof Gab Abramowitz from UNSW Sydney and Dr Aysha Fleming from CSIRO consider that nuclear power is not necessary for decarbonisation. Whereas Prof Abramowitz claims that “it is already cheaper to massively oversupply with solar and wind [...] than build nuclear infrastructure,” Dr Fleming remind us that “renewable energy and energy storage is available and can be used and developed.” Dr Grant Wilson from Birmingham University writes that it can be done “in the long-run,” but wonders whether “certain countries with a viable nuclear sector would wish to do so.”

Nevertheless, other experts disagree. Prof Dennis Hartmann from University of Washington claims that “it would be much harder to reduce carbon emissions without nuclear power,” and suggests “safer and more efficient nuclear power plant designs” as a way of keeping nuclear power and thus help decarbonisation. Adding to this, Dr Adriana Gomez-Sanabria from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria argues that nuclear power plays “a central role in the decarbonization of the energy systems.”

Finally, Prof Steven Sherwood from UNSW Sydney can envision decarbonization without nuclear power but explains that “nuclear power would be a useful transition technology for countries that do not have enough sunlight and wind compared to their population size.” He also reminds us that emerging technologies “such as nuclear fusion, steady improvements in energy efficiency, carbon capture and storage, etc.” may also help.

CONSENSUS

Would switching to organic farming cut greenhouse gas emissions?

Organic farming is an agricultural system that aims for a more natural way of farming through crop rotation methods and the usage of organic fertilizers. It has been shown that organic farming increases biodiversity and reduces soil erosion but its capacity to fight climate change by reducing greenhouse gases emission is controversial. Such controversy is also reflected in the answers we gathered but overall organic farming does not likely benefit carbon emission.

Prof Hartmann writes that organic farming has important advantages such as “zero tillage, storing carbon in the soil and less use of fertilizer derived from fossil fuel,” so it can be an option to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Dr Fleming agrees with the idea that “reducing nitrogen fertilizer is helpful to reduce emissions,” but she also considers that this “wouldn’t be enough alone.” Dr Gomez-Sanabria highlights the reduction in the “consumption of artificial fertilizers and pesticides” as well as the capability of organic farming to sequester “more carbon in the soil than conventional farming.” Dr Adrian Muller from Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL admits that soil organic carbon sequestration “tends to be higher in organic than in conventional systems.” However, he also explains that “soil organic carbon sequestration is [...] not identical to emission reductions, as it absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere instead of avoiding its emission at the sources.”

In terms of volumes, it seems clear that a switch to organic farming would not help greenhouse emissions and most likely be worse. Some experts consider that organic farming would not be able to have any real effect on greenhouse gas emissions if the whole planet were to switch to organic food. Prof Guy Kirk from Cranfield University recognises the many “local environmental benefits to organic farming practices, including soil carbon storage, reduced exposure to pesticides and improved biodiversity.” However, he explains that “these potential benefits need to be set against the requirement for greater production.” Given the fact that organic farming requires more land, crop expansion to make up for this may not only “increase greenhouse gas emissions” but also impair “greater carbon storage under natural vegetation.” Dr Muller also questions that organic farming will cut greenhouse gas emissions, although he argues that “it would neither lead to an increase,” due to the fact that “increased land use on the one hand and reduced nitrogen use and the ban on mineral fertilizers on the other work in opposing directions of increasing vs reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

Quick Answers

Is it too late to prevent climate change? No. Human-caused climate change is already happening, but experts insist that it is not too late to prevent more extreme change - and the damage that would come with it.

Are some people already being affected by climate change? All our experts agree - that is absolutely the case. Extreme weather events such as heatwaves, floods, droughts or cyclones are now more intense and frequent, the sea level rise is already affecting low-lying coastal communities and animal habitats have shifted. The latest IPCC Assessment Report includes details on this.

Is having 100% renewable energy for a country feasible? According to our experts, there are currently no technological barriers for transitioning to a 100% renewable energy regime. However, they all agree that other economic, political and social aspects may become an issue and should be worked out.

Has the Amazon become an emitter rather than sink? Yes, research from 2021 indicates that parts of it now emit more carbon than they can absorb. Deforestation and wildfires are the main culprits, along with the drop in photosynthesis and the higher tree mortality caused by climate change.

Does planting trees help reduce climate change? Because trees use atmospheric CO2 to grow, they lower atmospheric levels and limit climate change. Still, experts also warn about the importance of knowing where we plant such trees and what species we should use. For example, planting exotic pines in peat bogs reduces biodiversity and the peat’s ability to sequester carbon.

Does cattle livestock contribute 51% of human-derived greenhouse gas emissions? No. This claim quickly made it to the headlines some time ago, but can be traced back to a 2009 non-peer-reviewed study in which dubious CO2 sources were included. More accurate estimations concluded that livestock does account for around 18% of global human-derived greenhouse gas emissions, however.

TOP ANSWER

Is there evidence that climate change is impacting the Great Barrier Reef?

Climate change is causing sea temperatures to rise, which causes significant damage to corals. Corals are damaged by bleaching, where in high temperatures they lose their symbiotic zooxanthellae and are no longer able to photosynthesise. The death of many corals as a result of this process causes the whole ecosystem to collapse. In some areas of the Great Barrier Reef, around 80% of the corals died in the space of several weeks in the 2016-2017 bleaching event. The increasing frequency of bleaching events due to climate change, and the damage that they have on the Great Barrier Reef and other reefs worldwide, are well documented in rigorous peer-reviewed research such as Hughes et al 2018 (Science), Hughes et al 2017 (Nature), and Ainsworth et al 2016 (Science).hol.

Dr Timothy Gordon

An expert from University of Exeter in Marine Biology

Takeaways

Climate change is happening now, and many are already experiencing it through more intense and frequent heat waves, floods, droughts or storms.

Climate change is already inevitable, but the extent to which temperatures will rise remains within our control. While it’s almost impossible to avoid the 1.5ºC, we could prevent further increases if we act quickly.

Nuclear power would help in decarbonising our energy sources, although we might get away without it if renewable energy sources are rolled out at scale.

Running a country with 100% renewable energy is already technically possible but economic, social and political hurdles slow the way.

Large scale organic farming is likely not good for carbon emissions. It may help by enhancing soil carbon storage or lower use of fertilisers, but comes at the bigger carbon cost of much greater land use.